Oh dear...

This new series inspired by blog poster Bob.

Ashiwaza are some of the most sublime and simultaneously frustrating techniques in the whole of Judo, except of course when butchered as in the photo above.

However, a lot of people tend to be rather fuzzy on what exactly the differences are between certain ashiwaza, what the principles behind them and the implications for the execution of the throwing action are.

When looking for reference to a technique or to clear up any confusion. You first go to, should be the Kodokan’s nage waza guide hosted on youtube at user tambietem’s channel

So many of your questions may well be answered by this video:

Some of them may not be though. So I will do a little exploration of the main ashiwaza and split them into groups where I believe the greatest potential for confusion lies. This is not a how to or proper breakdown of the techniques merely a cursory overview to help show the differences in principle and application of the techniques.

Ko soto gari and De ashi barai - What’s the difference?

The route of this confusion is between what constitutes Harai and Gari. Most often this is found in the question of whether a throw is a Ko soto gari or De ashi barai. People will often say the difference lies in whether uke's foot is taken in front of them or straight forwards.

De ashi barai

As opposed to, Ko soto gari

However, this can't be the case because in Harai tsurikomi ashi uke's foot is taken behind them and in O uch gari uke's leg is taken out to their side. So direction of leg movement is not the contingent factor for Harai or Gari classification.

O soto gari, O uchi gari, Ko uchi gari and Ko soto gari all have one consistent principle that is that the majority of uke's weight should already concentrated on the leg that is attacked.

O soto gari, O uchi gari, Ko uchi gari and Ko soto gari all have one consistent principle that is that the majority of uke's weight should already concentrated on the leg that is attacked.

However, as many people know if you try and perform a De ashi barai on a foot that the majority of uke's weight is on then nothing will happen.

That is because the throwing principle behind Harai is weight transfer. The leg should be attacked as the majority of uke's weight is about to be transfered to or away from it. This is why Harai waza are much harder than Gari waza as the timing finesse in the fractions of a second when weight is about to be transfered away from or to a leg, is much more difficult to sense and react in time to.

And although all Judo techniques when performed in ideal conditions should be effortless the application of force to throw an opponent when the majority of their weight is already planted is greater than that when they are about to transfer their weight to or away from a leg.

That is because the throwing principle behind Harai is weight transfer. The leg should be attacked as the majority of uke's weight is about to be transfered to or away from it. This is why Harai waza are much harder than Gari waza as the timing finesse in the fractions of a second when weight is about to be transfered away from or to a leg, is much more difficult to sense and react in time to.

And although all Judo techniques when performed in ideal conditions should be effortless the application of force to throw an opponent when the majority of their weight is already planted is greater than that when they are about to transfer their weight to or away from a leg.

A good way to envisage the difference is if you imagine walking down a set of stairs in the dark. As you move down the stairs you weight your foot in expectation of planting your foot on the step. So when you reach the bottom of the stairs and think there’s an extra step when there isn’t you weight your foot expecting it to reach solid ground at a certain point yet you don’t. The result is you fall. This is the essence of De ashi barai, uke expects for his weighted foot to contact the mat but at the vital second you sweep it out and uke falls.

A good way to envisage Ko soto gari is to stand up and allow yourself to rock back onto just your heels. Probably best to this near to a wall or something to grab onto... Then try it again excepting rocking back so that just the heel of one foot is supporting all your weight and in contact with the ground. Then think about how little a clip or reap it would take to make you fall.

Okuri ashi barai, Sasae tsurikomi ashi and Harai tsurikomi ashi - What’s the difference?

Okuri ashi barai, Sasae tsurikomi ashi and Harai tsurikomi ashi - What’s the difference?

As noted in the above examination of the differences between Ko soto gari and De ashi barai a key indicator of the difference between the throw can lie in the words that make up its name. In this case we have two throws that have ‘Harai’ in the name and two throws with ‘tsurikomi’ in the name. However, despite these crossovers the three throws couldn’t be more different.

Okuri ashi barai - translations of this technique’s name range from double leg sweep, to sending foot sweep, to assisting foot sweep. I’m not going to pretend I know the definitive translation, as I speak no Japanese. However, I understand enough to know that two of the defining aspects of this technique are that both feet are swept together and simultaneously and that it is a harai action.

So this means as explained above that the attack must come as a foot is either weighted or un-weighted and in addition that during the attack uke’s feet must come together as part of the sweep.

What is critical, however, is that there is no blocking action and no tsurikomi action to the technique.

Sasae tsurikomi ashi – sasae comes from sasaeru which means to block, tsurikomi is explained here and ashi means foot or leg.

So the critical factor to remember is that you should concentrate on applying the tsurikomi action, which should ensure that the majority of uke’s weight is forward and over his toes, whilst applying a blocking action to uke’s leg.

As a result Sasae tsurikomi ashi is usually done when uke moves forward/ shifts their weight forward or moves in a circular direction which leaves them out of equilibrium and their weight forward. Critically the blocking action should, ideally, occur in the middle of the process of weight transfer. So as uke un-weights his foot as he lifts it off the ground to advance, the blocking action should ideally come between his advancing foot passing the placed foot and the advancing foot being placed on the ground and becoming fully weighted.

Attempting to apply Sasae tsurikomi ashi when the foot is planted and fully weighted will usually prove ineffective unless your opponent is poor or you tsurikomi action very very powerful.

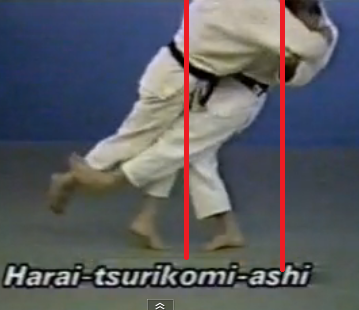

Harai tsurikomi ashi contains the similar tsurikomi element, however, without the sasaeru element.

Note, it is important that in Harai tsurikomi ashi you attack only one foot, the retreating foot, whilst applying the tsurikomi action.

Harai tsurikomi ashi is nearly always executed when uke retreats, this isn’t always an obvious retreat as in uchikomi or nagekomi. However, the principle, of retreat remains a constant. This is probably one of the hardest throws in Judo so if you struggle with it, don’t be disheartened.

As uke retreats his weight tori applies the tsurikomi action shifting uke’s centre of gravity out and forwards. Whilst simultaneously entering and sweeping in the Harai fashion to accelerate the retreating action of uke’s foot so that it doesn’t touch the ground.

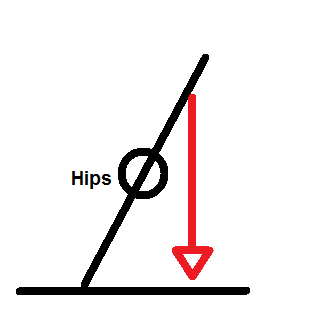

At this point the effect is as if uke’s weight has been loaded onto tori’s sweeping leg and hip, momentarily.

The red line indicates uke’s new centre of gravity

Uke’s centre of gravity in relation to tori

The most common confusion arises between Sasae tsurikomi ashi and Harai tsurikomi ashi especially when performed with oikomi entries from unusual grips.

Here’s an example of a technique easily mistakeable for a Harai tsurikomi ashi, which is in fact a Sasae tsurikomi ashi

Its not until the final slow motion angle at 1:05 that you can clearly see that the leg is being used in a blocking or supporting action rather than in sweeping action, clearly making the technique Sasae tsurikomi ashi.

If you’re wondering why Muneta has Pikachu on his gi, it’s because he’s a big fan of Pokemon.

Sasae tsurikomi ashi and Hiza guruma - What’s the difference?

Another commonly confused pair are Sasae tsurikomi ashi and Hiza guruma due to their superficial similarity in a competition or randori. Most coaches will say that the key difference lies in whether the technique is applied to the knee or the shin and that would appear correct as Sasae tsurikomi ashi is always demonstrated on the shin and Hiza guruma, well its the Knee wheel so obviously its on the knee, duh.

However, you can apply Sasae tsurikomi ashi to uke’s knee and Hiza guruma to uke’s upper thigh - Daigo Sono san.

As I’ve already explained in depth the key principles underlying Sasae tsurikomi ashi, I will concentrate on Hiza guruma.

The most important difference in principle between the two techniques lie in the difference between the throwing action inherent in the sasaeru action and the kuruma action. Note that it is a convention to romanize the Japanese verb with a ‘g’ when following a vowel, however, to leave it as the original ‘k’ sound when it isn’t following a vowel i.e Harai goshi and Koshi guruma. Both share the word ‘koshi’ or hip when it follows a vowel it is Romanized with a ‘g’ when a standalone word it retains the original ‘k’ sound.

As explained sasaeru means to block or sometimes to support. Kuruma means to wheel, specifically to wheel around a fixed point. If you think that blocking and wheeling around a fixed point is some anal and esoteric distinction, then step back and think what other techniques are kuruma waza – Kata guruma, Koshi guruma, Ashi guruma, O guruma and O soto guruma. If you tried to ‘block’ with those techniques your throw would be a disaster, in all you must pivot around a fixed point whether it be shoulders, hips or leg. The same applies to Hiza guruma.

Most of the Kuruma waza where uke is pivoted around a leg are rare in competition because the immense difficult of pulling them off, Hiza guruma is one of them. A rare example pulled off by Delgado of Portugal shows quite well how uke is truly pivoted around the leg, rather than the leg blocking uke.

So if you attack uke’s leg and make contact at the knee, but the throwing action is effected by a block then it is a Sasae. If you make contact on the shin, but the throwing action is effected by pivoting uke around a fixed point then it is a Hiza guruma.

Now this is a very fine definition to draw in a competition and frankly the classification doesn’t really matter that much. However, where this distinction is important is in developing your own understanding of the principles of the two techniques so that you can understand what principles make the two throws different and so better apply the techniques.

More ‘What’s the difference’ to follow covering; Uchi mata/Hane goshi, Seio nage/Seoi otoshi and more upon request.

Awesome! You've answered my question, and then some. I'm looking forward to your coming "What's the difference" articles.

ReplyDeleteI actually am not that clear on the difference between okuri ashi barai and de ashi barai. Any note on the matter?

ReplyDeleteWith Okuri Ashi Barai you weep both opponent's feet. Timing is very important, Okuri Ashi means somthing like "sliding foot"...

ReplyDeleteI would eprimere my opinion on the difference between de ashi barai, ko soto gari and ko soto gake.

ReplyDeletePeople walk (as everyone knows) by passing the weight from one foot to foot. This means that for example the weight goes from left to right, passing between the left and right.

When you walk to the front, the weight from left foot ends on the right, when the right foot lands the potential energy of the falling body is transformed into kinetic energy, at that time sweeps (short motion, circular, almost straight) and becomes de ashi barai (ie a sweep to one that advances).

When instead there is no forward movement of uke, you can mow the right foot (the movement is broader as a sickle) taking advantage of the weight shift from left to right even if the foot does not land (but from a dynamic point of view and pretty much the same thing, because the energy / weight comes on the right foot and sweeps the moment arrives), the feet of bulls are generally more distant from each other and the result is a larger movement (mown).

To summarize: with de ashi barai is a foot forward, with ko soto gari not.

In both cases, it uses the energy that arrives.

P.S. And 'possible to pull ko soto gari also with the weight that goes away from the right foot to the left. If you do this thing with de ashi barai you are always an effective barai, but not orthodox, because the foot moves back and not forward (de = advancing).

When there is the movement towards the front or behind (ie uke takes a step) it is possible to attach the foot during weight transition between one foot and the other, in this case locks and pushes with the foot, but the movement carries the weight uke upward (then down) not downwards as is the case for de ashi barai and kosoto gari.

Thanks for the hospitality.

Greetings

I really appreciate this. I am a yellow belt and working very hard to understand the terminology. Thanks, this is so helpful.

ReplyDelete