The biggest bane of a beginner Judoka’s life is when standing randori rolls around. When facing black belts this means lots of airtime and tough landings. When facing other beginners it means the exhausting and dispiriting process of trying to do anything you’ve been taught as your partner shoves two iron bars in your chest and moves their entire lower body and legs as far away from you as possible.

All the throws you’ve been taught where your partner stands up right and you’re able to enter and get underneath now seem like they were dreamt up by some fantasist who’d never even seen a randori let alone done one.

You are encountering the number one enemy of aspiring Judoka everywhere – stiff arming.

There are countless threads on Judo related forums across the internet where beginners seek to find answers to this problem in those threads there is some good advice and some bad advice.

The number one piece of bad advice given is that of the silver bullet.

Anyone who tells you that the solution to stiff arming is to be found in a single technique is misguided. The solution to any beginner’s problem is never found in a single technique it is always found in the fundamentals.

The Club

Perhaps the most dispiriting aspect of stiff arming is that the main solutions to it lie outside of the control of a beginner and firmly in the hands of an instructor.

The main ways to overcome stiff arming during randori are:

· Ensure falling confidence through good ukemi training

· Instil trust in partners through properly supervised nagekomi

· Instil control in throwers to ensure safer landings and easier ukemi

· Delay standing randori, concentrating on newaza randori, ukemi, movement skills and nagekomi. Until a basic competence in falling and controlling an uke have been established.

· Supervised randori so that people are matched with partners who can practice with them safely and those who’re stiff arming or purely being defensive are reminded and encouraged to be positive.

However, as a beginner you have no influence over how a club is run, nor do you have the technical knowledge or technical ability to run or design these drills.

You

Probably the simplest thing you can do is to be selective about who you practice with everyone knows who the worst stiff arm offenders are and those whose idea of a standing randori is stomping around for five minutes, like a zombie bent over at the waist. Try and minimise the number of practices you have with these guys try and fill your randori slots with positive Judoka, usually these are the higher grades.

This of course may not be feasible in a small club with say only 10-15 members. In this case the number one thing to do is to communicate with your partner. Don’t lecture, don’t hector, don’t try and come off as their superior giving them instructions. However, try and suggest in a polite, constructive and humble way that you would like to do a more positive randori and focus on not being defensive and would they try and help you out. Also try pointing out politely how it’s not only wasting your practice time, but also theirs if they just spend 5 minutes being defensive without ever attacking.

If you feel able to without coming across as an arse, try and have a word with your instructor to see if they can help you out by cracking down on stiff arming with reminders and encouragements to be positive.

Of course there are those who simply won’t listen to polite reason, or to coaches. In this case I suggest a firm, open palm slap to their annoying twat face.

Alternatively...

Movement

You can try using movement to create opportunities to get around stiff arms.

Now I have previously talked about T-ing up extensively and reference it quite a lot.

If you’ve been following since the beginning on Bullshido then you should have had a few months of practicing this under your belt and it should be starting to sink in. If not and or you haven’t read that article, first read it and then come back to this.

Now here’s an example of how to take the principle of using movement to break down Jigotai, but apply it in a totally unrealistic way.

My issue with this video is that it assumes that a partner will move in a way that catastrophically destroys their balance and will remain there whilst you move around them. In a way its the Judo equivalent of this:

Probably a little harsh, but you get the general idea. Unrealistic reactions from an uke lead to unrealistic responses from tori in a way that makes the application of what is taught unworkable in an alive scenario, like randori.

A much better example is the first minute and a half or so of this old favourite of mine

As I’ve already spent time breaking down and explaining that video in the T-ing up thread I won’t repeat myself here. Except to say that the more you move and importantly the quicker you move the less effective stiff arming will become and the more opportunities will present themselves. Of course you must match your tempo to your ability and size what is moving quickly for a 66kg/145lb 2nd dan is completely different from what is moving quickly for 100kg/ 220lb green belt. So don’t go crazy trying to spas run round the mat, keep controlled, keep a good grip and just step up the pace of your normal movement patterns.

Ashiwaza

Although there is never a one technique answer to a beginner problem or even a group of techniques. In the case of stiff arming and purely defensive postures ashiwaza can be useful. Although they’re not always useful, if you’re 5ft 7 trying to do ashiwaza on a guy who’s 6ft 2 and stiff arming whilst bending over, ashiwaza are obviously not going to help you. Flapping your legs around a metre away from their ankles is obviously going to achieve nothing and be just as frustrating as the stiff arming.

If you’re thinking at this point, hold on, my coach is 5ft 7 and I’m 6ft 2 and he’s always foot sweeping me. Well your coach is probably at least a 2nd dan with 10-20 years Judo experience. So this is one of those situations where a massive technique gap can overcome a physique gap.

So, when there isn’t a massive size disparity they can come in useful. This is because you can disrupt your opponent’s movement and stepping patterns that open up opportunities for throw attempts. Ashiwaza also tend to have the effect of relaxing their arms as your partner worries about their feet more than their upper body.

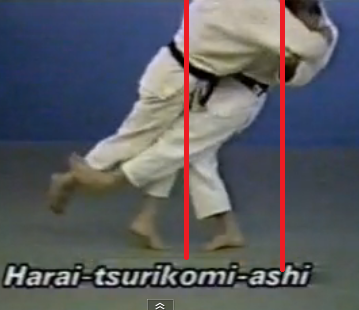

Pretty much all of the ‘minor’ ashiwaza are applicable:

De ashi barai

Ko soto gari

Sasae tsurikomi ashi

Okuri ashi barai

Ko uchi gari

Remember to try and stay controlled and not just wildly hack away at your partners ankles, easier said than done. To ensure that you’re on balance and capable of reacting to any opening your attack may create.

Grip fighting

I’m a strong believe in beginners minimising the grip fighting that they do during randori. Note that I have quite specific definitions for what I consider to be grip fighting and two categories within that as opposed to gripping.

To me gripping is the key concepts of control over your opponent using the gi eg. breaking your opponents posture whilst keeping the elbow down with a high collar grip, turning the palm outwards when gripping the sleeve to maintain control over your opponents hikite etc...

Grip fighting is the actual act of seeking, breaking or avoiding a grip. To me grip fighting can be broken down into positive and negative grip fighting. Positive grip fighting is where you break your opponents grip, or use grip fighting techniques to actively achieve your desired grip with the intention of throwing. Negative grip fighting where you just try and frustrate your opponents Judo without seeking to obtain you ideal grip in order to throw your opponent.

Negative grip fighting has no place in a beginners randori experience.

However, sometimes it is an option to consider to break your opponents grip in order to facilitate you attacking and throwing them. I think for a beginner this should only be done in extreme situations where your partner is being excessively defensive, won’t listen to you or your coach and all your positive attempts to use movement, ashiwaza etc... have failed.

Tricks

Note these are tricks for a reason, they are not long term solutions to the issue, they are tricks.

Against a left hander, as a right hander, you should always endeavour to have the inside grip, by which I mean this.

From here, against a left hander you can raise your elbow to break the strong structure of their arm to give you space to apply the proper tsurikomi action like so.

It should go without saying that this is only really applicable for forward techniques.

An alternative trick is to apply a small amount of upwards pressure to uke’s elbow joint to cause a relaxation in the arm to relieve pressure and create an opportunity for an attack

Don’t try Sutemi waza and Makikomi.

These are often very popular suggestions on internet message boards, however, they are not good suggestions. The idea stems from a faulty logic that uke is leaning totally forward and so in keeping with the philosophy of Judo that softness should give way to hardness i.e if pushing forward you should just go with the push and you will throw them.

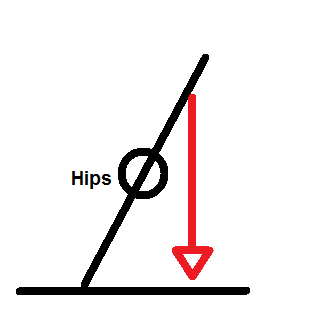

This is based on a fundamental misunderstanding of the mechanics of the throws suggested and also the balance of uke when they’re bent over in a stiff arm position. When uke is bent over and stiff arming their entire weight is being transmitted straight forward into tori. It is actually located underneath their stomach/chest.

Now this would seem to facilitate ideally a sutemi waza attack, however, because of the stiff arms tori is unable to actually get underneath uke’s centre of gravity. Getting underneath a partners centre of gravity for a sutemi waza is as hard if not harder than getting past their arms for an Uchi mata.

So what happens in a makikomi attack is that tori either twists uke and they both fall straight forward, uke rolls out to side of the attack, or if there is a major size and weight advantage on tori’s behalf uke gets wrapped around them and rolled over.

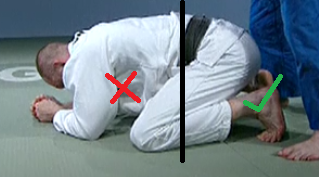

In a sutemi waza tori tries to get in under uke’s centre of gravity, but because of the stiff arms and inexperience ends up just dropping straight down onto their arse. Usually uke will flop or sprawl ending up on top of tori, will flop/ sprawl out to the side of tori occasionally landing on their side, or if there is a major size and weight advantage on tori’s behalf uke gets taken over by the momentum and rolls over and onto their back.

This is not good Judo, nor is it a beginner attempt at trying to work towards good Judo. It’s just bad Judo all round and should be avoided if you want to make real progress in Judo.

Don’t try Standing armlocks and strangles

Standing armlocks and strangles are very difficult and very dangerous techniques.

I’ll repeat that.

Standing armlocks and strangles are very difficult and very dangerous techniques.

Standing armlocks in particular are incredibly dangerous, they are very easy to apply sloppily, very easy to apply with too much force, without control and very difficult to submit quickly enough to.

This is inevitable if you start doing standing armlocks on all and sundry

Please don’t try standing armlocks and strangles on people to get them to stop stiff arming, it is very dangerous and is going to end badly.

Hopefully that has been fairly comprehensive and has given you some positive ideas about how to deal with a stiffy as well as some ideas about practices to avoid.