So often when we practice Judo we do each segment of the Judo match in isolation- gripping is done separately from throwing, throwing from moving, tachiwaza from newaza. However, in a contest we have to be able to do all of these things seamlessly being able to grip, move, throw and transition into newaza without pausing significantly in between.

Coaches often therefore use training exercises to help people chain together the separate aspects that we usually train often in isolation. They will use drills where you break a grip, move, T-up and throw and as concerns this article they will use drills that try and replicate the transition from standing into groundwork.

In between the application of a throw, tachiwaza, and the application of a roll, strangle, pin or armlock – newaza- is the transition.

Conceptualising the transition

As I have been taught there are two key elements to the transition they are the connection and the catch. Note that I’m not referring to throwing situations where tori attempts a throw and lands in a pin or where uke becomes tori, during the throw, and lands in a pin. I’m talking about situations where a throw is not applied in a controlled fashion that lands tori in a position to apply a pin.

In these situations there are two key concepts:

The Connection

The Catch

The Connection

As Adams explains and demonstrates above after having performed a throw it is vital that tori remains in contact or connected to uke in order to place himself in the best place to then attack further in newaza.

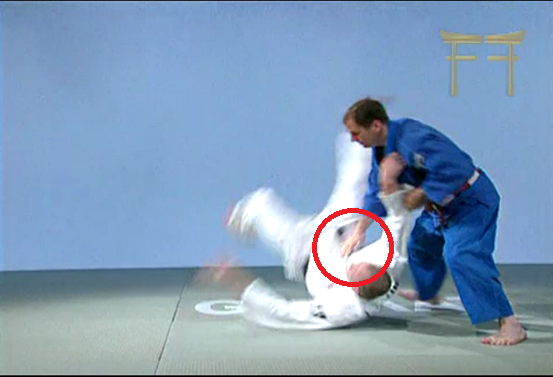

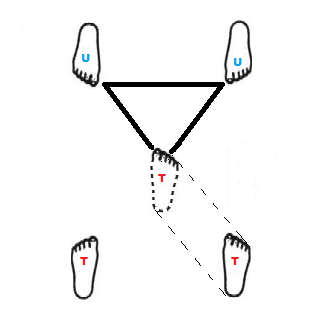

Tori throws uke and releases his grip on the lapel, whilst maintaining hand contatct:

Tori’s hand moves from the lapel to uke’s lat muscle and retains control and grip of uke’s sleeve

As uke continues to roll from the throw, tori retains contact with his tsurite hand on uke’s lat muscle and his hikite hand moves to uke’s shoulder

As tori does so he manoeuvres around and with uke so that he retains contact.

Tori continues to stay with uke and finishes in a strong position ready to attack

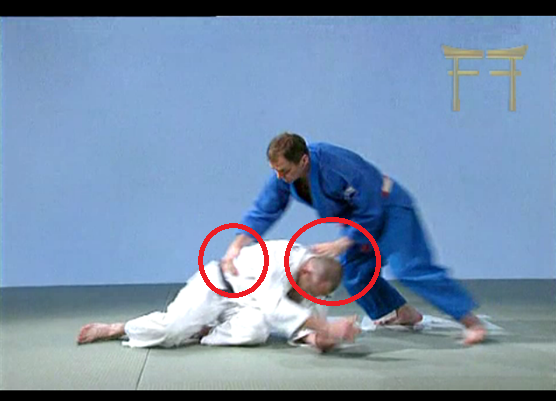

Here are some examples of tori staying to uke in a contest situation

The Catch

Once you have stayed connected to uke its important that you’re able to attack swiftly and purposefully.

In order to go from being connected to uke and in a good control position to an attack you must ‘catch’ a control point.

A catch comes in many forms and some catches can lead to many techniques and entries.

A hook is a not the same as a catch.

Although a hook is often an excellent precursor to establishing the catch.

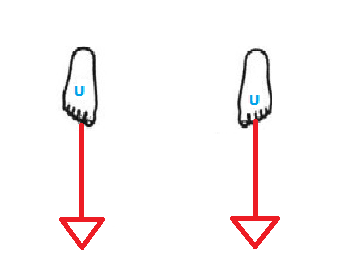

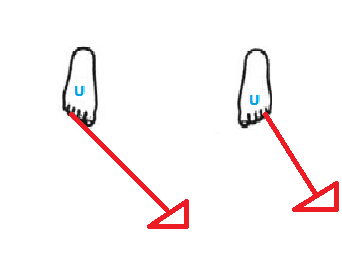

The catch is a grip on the collar or arm.

A common catch, for Judo, to start turnovers into pins and armlocks is on the collar

Another is on the forearm

And of course one of the most famous catches of all, in the crook of the elbow, for Adams Juji roll

Another common catch is to send the arm to catch the collar in order to tighten it for applying a strangle.

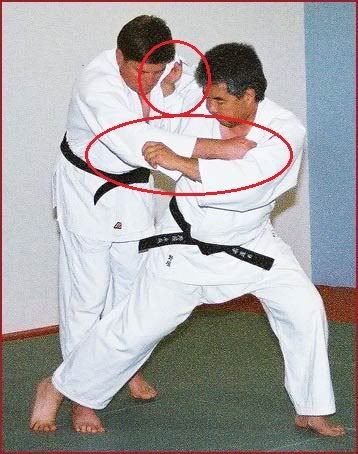

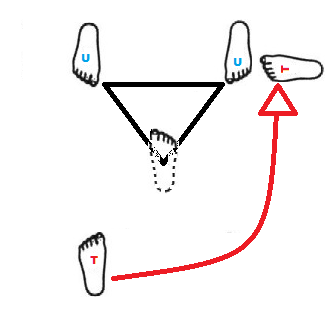

Tori grasps the collar slightly lower than normal

Tori then brings in the hand that he intends to apply the shimewaza with so that two hands are on the collar

Tori then uses the lower hand, that established the catch to tighten the jacket and thus the shimewaza

Staying connected to uke and getting the catch demonstrated in competition

Practicing the transition

In my opinion practicing the transition from tachiwaza to newaza is as important as practicing the respective parts of Judo. In every competition you enter at some point you will throw imperfectly and need to know how to effectively control the transition and then attack in newaza.

I believe the best way to practice the transition is progressively. That is to stay in a controlled and pre-determined way that builds fundamental skills and then develops them in a planned and structured way.

First and foremost is understanding how to throw and throw with control and to understand how to apply a selection of turnovers.

So once you know how to throw safely and in a controlled manner and have learnt a selection of turnovers you can begin practicing transition training.

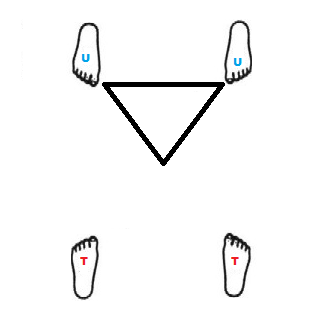

Normally the core of transition training is attacking the turtle performing uchikomi until all aspects of the attack against the turtle and well in grained

After that it’s important to practice the throw and connection

Once accomplished at those you begin practicing the entire sequence – throw, connect, catch, turn, pin/submit, ippon.

This training methodology can be refined, personalised and specified so that if a player is good at the turn in uchikomi and is good at connecting with uke in live situations, but struggles with the catch in live situations.

Then the drill can be refined so that it becomes; throw, connect, catch, reset thus drilling the catch reflex to improve it.

This training can then shift phase, all above examples are of cooperative training, but as skill, competency and fluidity increase resistance can be progressively added to the drills until finally you reach a full randori situation with a continuation into groundwork permitted.