Kosei is sad!

Kosei is sad, because he wants to do Judo, but can’t because he has no one to practice with.

Now Kosei is happy!

Kosei is happy, because now he has a partner, he can practice Judo.

To do Judo, takes two people.

To learn Judo, takes two people working together

In order for a beginner to learn Judo its vital that they have a good uke. And as the beginner progresses through being an intermediate to being advanced the importance of them working with a good uke not only remains, but the importance of them being a good uke becomes ever more important.

So how do you become a good uke?

Well it starts with the foundation...

Ukemi

Ukemi is the foundation of being a good uke because fundamental to being a good uke is confidence in being thrown and being comfortable going over.

If a beginner doesn’t learn to be good at break falling and comfortable being thrown they will never become a good Judo player and will probably drop out of the sport.

Central to ensuring good ukemi in beginners is regular practice and appropriate practice.

Appropriate practice should also be matched with appropriate pairing.

Appropriate practice

White belts should not be made to take falls from complex throws early in their Judo experience.

Rather the amount of time they are actually thrown outside of highly controlled circumstances should be minimised

Appropriate pairing

There’s never a scenario where a white belt should be paired with a black belt for the black belt to practice full commitment nagekomi. This is an example of inappropriate pairing.

It’s also ideal to avoid pairing white belts with other white belts for nagekomi. However, in small clubs or in beginner only classes this may be unavoidable.

Appropriate practice and appropriate pairing are important so that a beginner has time to develop their ukemi skills, before being thrown into the deep end and so that their early experiences of falling and being thrown are positive ones. So that they go forward associating falling and being thrown with safety and comfort, rather than pain, injury and danger.

If a basic competency and familiarity with falling is not established then a beginner will never be able to progress to the more advanced areas of being an uke.

YOU

Now naturally the above will be out of the control of you, the humble beginner, it will be in the control of your club coach/ that day’s instructor.

However, what you do have control over is your time management and your level of commitment.

Manage your time and demonstrate your commitment by turning up early and or stay late after each practice and spending 5/10/15 minutes practicing ukemi.

I know you’re busy, you have a job, kids, a WAG to please, but everyone can always make time. I’ll bet you can make time to go to the pub, make time to watch TV and make time to dick about on the internet like you are now- reading this...

You can make time either 5 minutes before or 5 minutes after practice to work on your ukemi.

A good Uke

What makes a good uke?

Aside from the obvious, being able to fall and take ukemi.

Being a good uke is actually quite a difficult thing to become, because the secret to being a good uke is understanding how the throw being practiced on you works so that you can then position yourself, react and allow yourself to be moved in the specific way that makes that throw easy to practice.

This is what makes being a good uke so hard for beginners as, because you’re a beginner you don’t have an understanding of how even one throw works let alone a wide variety of them.

You also may not have the fine motor skills and sensitivity of movement to position yourself and react in a helpful and constructive way.

Fortunately, however, as you learn more about Judo and, hopefully, get better at Judo you will start to understand how throws work more and more and so will learn what it is you need to do as an uke to help your partner – tori, achieve.

However, in the meantime between learning more about throws and understanding what it is you need to do and now. There are some major mistakes you can avoid and some things you can do to make life easier for your partners and thus make yourself a better practice partner.

Common errors

By far and away the most common errors beginners make when being an uke are Jigotai-ing and stepping off.

Jigotai-ing

Jigotai is Japanese and translates as something like ‘defensive posture’. Its characterised by bending at the knees and lowering the centre of gravity.

And will be familiar to anyone who has done Judo with a beginner.

Jigotai-ing is a natural reaction to someone trying to break your balance forward, because people who aren’t used to Judo don’t want to go off balance. As they’ve spent 20-40 years of their life learning not to fall over.

What makes Jigotai-ing such a problem for beginners acting as ukes is that it is so natural a reaction it is done unconsciously without the beginner realising it.

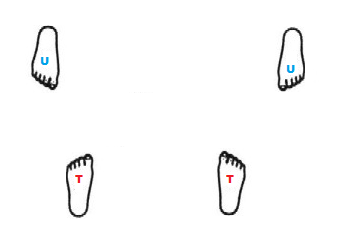

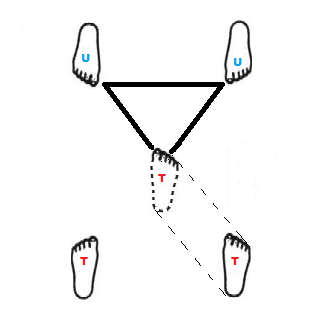

Here you see a stylised demo of a bad uke Jigotai-ing during an uchikomi session

Jigotai-ing is a natural reaction, but it is a natural reaction born out of fear.

A fear of being thrown, the more confident you are at being thrown i.e the better at ukemi you are. The more trust you have in your tori i.e working with a higher grade who has control.

Then you will experience less or no fear of being thrown and thus this natural fear reaction won’t happen.

However, you can’t overnight turn into a ukemi wizard who can float to earth like a feather rather than crash to it like a wounded elephant.

Nor can you always guarantee to be paired with controlled and considerate partners.

Thus you must take it upon yourself to stop Jigotai-ing and regulate yourself to make sure you aren’t Jigotai-ing whilst someone is performing uchikomi or nagekomi on you.

Want an incentive to help you ensure you do regulate yourself?

The more you Jigotai in uchikomi, the worse your partners techniques will be and thus the less control and ability to throw safely they will have.

This will get worse when it comes to nagekomi...

The more you Jigotai in nagekomi, the more your tori will have to power through to ensure the throw and the less control they will be able to exert. Thus the more likely you are to get hurt.

If you combine someone who’s never been able to perform a technically correct uchikomi because of uke Jigotai-ing. Then trying to power through his technically incorrect throw in nagekomi, because of uke Jigotai-ing.

You as uke are more likely to get hurt.

Stepping Off

Stepping off, like Jigotai-ing, is a natural defensive reaction to stop yourself being thrown. Its not only natural, but is effective being used often in randori to escape throw attempts.

Except in randori the objective is to practice attack and defence, in uchikomi and nagekomi as uke you aren’t supposed to be defending and thwarting your tori’s throw attempts you’re supposed to be enabling and assisting them.

An example of stepping off

Usually in uchikomi such an extreme stepping off is unusual and if a beginner was being that extreme they’d probably be asked to stop by their partner and definitely be on the receiving end of an explanatory lecture by an instructor on how to uke.

Normally, however, what you see from beginners is a more subtly but as hindering stepping off.

Uke will move their foot forwards with the sleeve pull of tori.

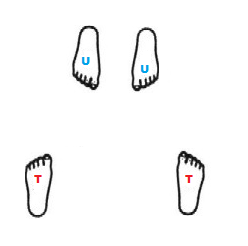

So that this sleeve pull

Will see a beginner uke actually step forward slightly as their upper body is pulled off balance.

This is, again, a natural reaction engrained through 20-40 years of learning that human beings shouldn’t fall over.

So they take a compensatory step forward to reset their balance, creating something like this

Which when you visualise how their hips are now set

Demonstrates how disruptive that is to a tori’s throw attempt.

Here we see stepping off combined with a throw in a static and moving nagekomi situation.

You will observe in both situations, moving and static, that uke steps forward slightly with tori’s kuzushi action to the sleeve hand.

This creating a gap between his planted and advanced feet, represented by blue and red lines respectively.

This changes his hip position and throwing angle, causing tori’s throw to look untidy.

Unlike Jigotai-ing, stepping off often means the throw goes awry, but doesn’t have as high injury potential as a result.

However, it is as annoying for a tori trying to learn and as detrimental to your toris development if you’re stepping off during uchikomi and nagekomi.

Again it is up to you to regulate yourself to ensure you aren’t stepping off.

If you think you may be guilty off this but aren’t sure call over an instructor and ask them to watch and see if that is what you’re doing and then get them to help you fix it.

The fix is, if you haven’t already guessed it...

More confidence in your ukemi and confidence in the control and responsibility of your tori.

The final major error is...

Stiff Arming

No, just no.

If you’re stiff arming during uchikomi and nagekomi you need a few of these

But how do I...?

Naturally as a conscientious person who wants to get better, well if you’ve been reading this article for this long you’re either conscientious and want to get better or really sad...

You will want to know how you can self-regulate and not commit some of the major uke-ing errors.

Whats, my first answer going to be?

Did you guess ‘More ukemi’?

Good.

Ok, but lets assume that after all my badgering you are actually doing as much Ukemi as humanly possible.

You’ve also picked the most controlled and responsible partner you can find to work with.

What next?

There are a couple of simple things you can do become a better uke.

Allowing yourself to be made ready to be thrown

The major or common errors I outlined previously all stem from a lack of willingness to allow yourself to be made ready to be thrown.

You will all hopefully be familiar with the 3 stage throw process

Kuzushi

Tsukuri

Kake

However, what many people do is only look at this from the perspective of a tori.

When doing Judo you will spend as much time as an uke as you will a tori so you will need to be able to look at a the throwing process from the other perspective.

To this end I propose this simplified process that an uke goes through:

Allowing yourself to be made ready to be thrown.

Being made ready to be thrown

Going with the throwing action

Taking ukemi

Now this is obviously not a perfect model, its my own back of a fag packet model. However, let’s just roll with it for now, for the sake of the article.

Of the four I would argue that three are active and one is passive.

The active three:

Allowing yourself to be made ready to be thrown.

Going with the throwing action

Taking ukemi

As they require consciousness, positioning, personal adjustment and specific movements by the uke.

The passive one:

Being made ready to be thrown

I.e having kuzushi and tsukuri applied to you are facilitate by your active steps, but are not ‘active’ in the same way as the other three.

So at this point lets pull back from theoretical waffling and look at some real world examples.

Now, because allowing yourself to be made ready to be thrown and Being made ready to be thrown are visual indistinguishable. The first being mental and attitudinal and facilitating the second.

One camera they happen as one, however, I argue for a beginner the ‘allowing yourself’ stage of consciously deciding ‘OK I’m not in danger, I’m not going to get hurt, I can get thrown safely and thus will allow myself to have my balance broken’. Needs to be acknowledged in order to be performed.

So in this visual example Uke is allowing himself to be made ready to be thrown and Being made ready to be thrown simultaneously.

And here he doesn’t do an exaggerated on tip toes action, but allows his upper body to come forward and his COG to be shifted.

An advanced Judoka like the tori in the video does these two things naturally.

However as a beginner you need to learn to psychologically and mentally reassure yourself of your safety and the lack of danger in order yourself to allow yourself to be made ready to be thrown and then as a consequence enable your tori to make you made ready to be thrown.

Understanding the throw being done to you

As I mentioned early on in the article, the hardest part about being a truly good uke, is that you need to have an understanding of the mechanics and workings of the throw that is being done to you.

Now, obviously as a beginner, there is no way you can know and understand every throw. I as a semi-competent 1st dan only know a bit and understand a bit of a handful of throws, probably fewer than 4/5.

However, you don’t have to know the ins and outs of every throw to be a good uke as a beginner.

You just need to keep some simple principles in mind.

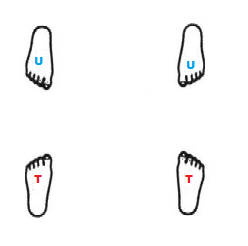

Feet shoulder’s width apart...

If you’ve never been told to stand ‘feet shoulder’s width apart’ you’ve probably not done Judo.

However, let’s think about this old maxim for a moment.

Why do we stand with our feet shoulder’s width apart and not say as wide apart as we can or even at a mere gnat’s crotchet width apart?

Well as it turns out shoulder’s width is a pretty ideal foot placement to allow tori to enter for most throws and for uke’s balance to be effectively broken.

So with that in mind lets think about foot placement.

If you’re static this is a relative non issue for most throws you just get to the old shoulder’s width and that’s it.

Add in movement, however, and a free flowing nagekomi session which moves around the whole mat. Or even a simple ashiwaza to major throw combination during which tori has to T-up.

Then you need to start thinking about your foot placement and your tori’s throw.

For example if you’ve just stepped off an ashiwaza or are moving around and your partner wants to do a Tai otoshi.

Having your feet spread wide apart is going to make it really awkward for them

Consider especially if your tori is shorter than you.

If you’re a lanky 6ft 3 working with a stocky 5ft 8 then you’re going to have to think that if they’re practicing Tai otoshi during a moving situation. Then you as the lanky one will have to appreciate that they need you to bring you feet close together or closer together than normal to help them do the throw.

They’ve got enough to worry about without having to do the splits, because you aren’t thinking about your foot placement relative to their throw and or stature.

Similarly if your tori is practicing a throw like Seoi nage they won’t want you to bring your feet together

And if we reverse the Tai otoshi scenario imagine now you’re the taller player having to work with the shorter one. You’re going to want a good gap between their feet in order to get in for your Seoi nage.

This also applies to drilling situations where you, as an uke, have to step off a major attack which is followed up by an ashiwaza attack.

If you step off a Tai otoshi and bring your legs close together when your tori wants to follow up with an O uchi or Ko uchi you’re being unhelpful.

So think about what throws your tori is going to be doing and how you should stand to best help enable them to do that throw.

Oh and btw, whatever you do. Do not google image search for ‘knees together’ with safe search off. Just don’t.

So on a characteristically high note let’s draw things to a close...

Conclusions

Ukemi

Ukemi and the confidence it brings when being thrown is what underpins everything.

If you can’t breakfall you can’t uke.

Self-regulation

Like those on Wall Street and in the Square Mile, I’m keen on self-regulation.

It is your responsibility as constructive member of your club and as a practice partner to ensure you aren’t making mistakes that you have control over.

However, don’t be afraid to ask for help and supervision. Like Wall Street and the Square Mile a bailout is only a request, or two, away.

Be Active not Passive

As an Uke you should be working almost as much as tori and you need to be concentrating just as hard.

There’s no point just switching off and thinking about what you’re having for tea. You need to concentrate on how you’re doing to ensure the best practice experience for your partner.

It takes two to Judo...

Think about your partner’s practice

What throws is he doing?

How should you position yourself for them – feet wide, narrow? Weight on the toes, the heels?

Should you speed up or decelerate relative to your tori? If so when?

Above All

Mutual benefit and welfare.

The better uke you are, the better your club mates will be.

The better your practice partners, the better you will get.

Greatness begets greatness.

Work on being a good uke, it will make you a better Judo player in the long run.